|

| Biographies |

Disorder and Surface Chaos

A caravan of Lincoln and Cadillac limousines coursed from Prince Nawaf Ibn Abdul Aziz’ palace, which is about the size of a New York City block, through the narrow streets of Riyadh and out into the desert. Behind them rumbled supply trucks, an electric-generator truck, a radio-communications truck and conveyances loaded with staff, servants and camp attendants. When Prince Nawaf, the brother of Saudi Arabia’s King Khalid, goes falconing, he doesn’t do it in a small way.

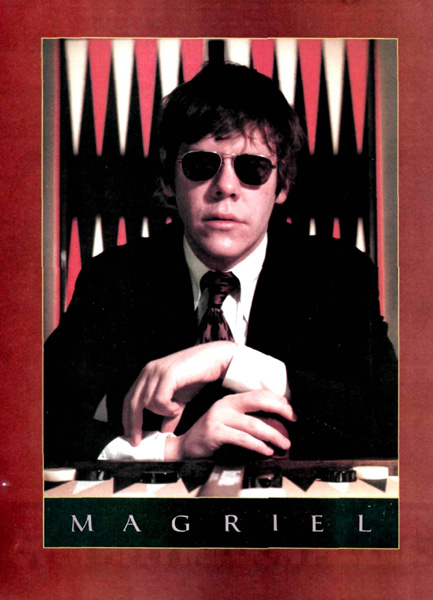

In one of the prince’s limousines was a man who was clearly a foreigner, although instead of his customary jeans and baggy sweat shirt he was wearing the traditional Arab thoub and ghoutra. He kept bouncing up to look out of the car windows with almost childlike enthusiasm. Everything interested him, even the nondescript dunes and the occasional aloe and tamarisk shrubs. His light brown hair fell over his forehead, and when he saw something that seemed to him remarkable, he would give his head a shake, so that his hair flopped. The man was Prince Nawaf’s backgammon teacher. His name: Paul Magriel. He was — and is — the world backgammon champion. Prince Nawaf does nothing in a small way.

Neither the prince nor the 32-year-old Magriel (pronounced Ma-GREEL) had known who the other was when they first met, late one evening in the fall of 1977 in a New York backgammon club. But the prince soon learned that the young man with the noisy crowd around him, women mostly, was already a legend in the game. He kept playing and playing and playing, and winning and winning and winning, and joking and laughing and flirting. He was known as X-22 and the Human Computer. He got these names in 1971 when he defeated the father of the modern backgammon renaissance, Prince Alexis Obolensky, on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten, to win the second major backgammon tournament he had ever entered. Since then Magriel has won or finished in the money in more than 50 tournaments, which he claims is a record.

|

|

|

Magriel’s most recent exploit was enhancing the good spirits in the club the night he met the prince. Not long before, Magriel and Roger Low, a 21-year-old backgammon whiz from New York City, had represented the U.S. in a three-day match against the best of Europe at the Mount Parnis Casino outside Athens. Their opponents were a pair of tough, experienced gamblers whom most devotees of the game considered the finest players on the Continent, if not the world — Joe Dwek of London and Kumar Motakhasses, a Londoner of Iranian birth. It was the opinion of European experts that Dwek’s brilliance with the doubling cube — a crucial factor in modern backgammon — and Motakhasses’ mastery of movement of the checkers would undo the young American ex-mathematics professor called the Human Computer, and the unknown kid he had brought along as a consultant. But after falling behind at the end of the second day, the Americans spent the night in Magriel’s room at the Grand Britannia Hotel reappraising their strategy. The result was a rally and a 63-61 victory.

“Magriel and Low were fantastic ambassadors for their country in every way,” says Lewis Deyong, a backgammon expert and author. “The Greeks were very impressed. They thought Magriel had some sort of incredible system based around mathematics, which he himself is the first to say is not the case. Nevertheless, out there they want to believe it because it makes an entertaining myth.”

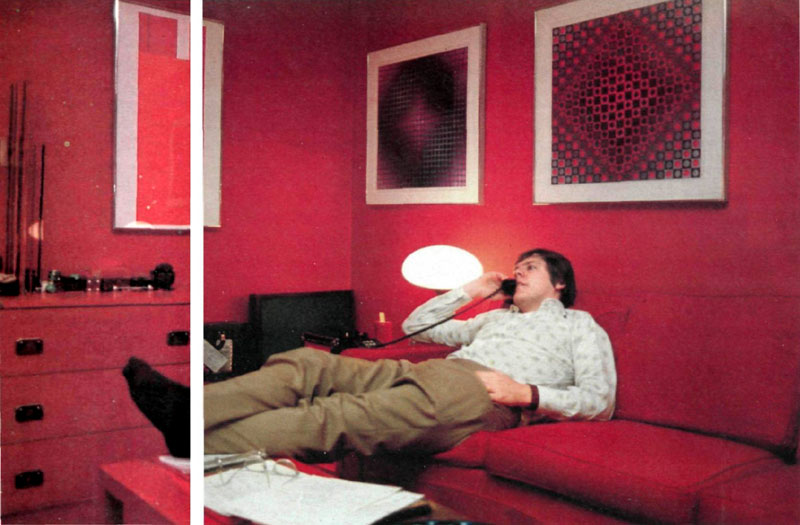

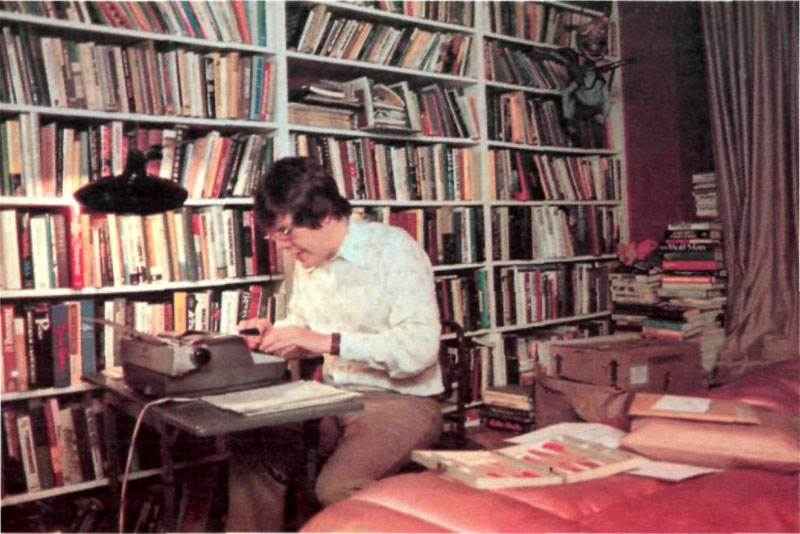

Magriel is a man of seeming contradictions. He has studied math at NYU and Princeton and taught the subject for seven years at the New Jersey Institute of Technology — yet he insists mathematics is the least important aspect of his game. He is painstakingly methodical and thorough in his approach to backgammon, sometimes spending several days analyzing a single play — yet his life is a jumble of loose ends and unfinished projects. He is diffident and introverted — yet he seems to want to turn his mind inside out, like a rubber glove, if only he can find the right words and the right person to listen to him. He is given to spending days on end by himself in his book-lined, television-less Manhattan apartment, having his meals delivered and reading Karl Popper and Rudolf Carnap, or writing, or simply thinking — yet he will play backgammon for 72 hours straight, or party for days or take a whirlwind trip to Chicago or Vienna or Los Angeles or Milan to participate in a tournament, during which he will talk nonstop and go without sleep.

Magriel's bachelor apartment in Manhattan does not contain a TV set.

On the living-room walls are two signed Vasarely prints and one Anuzkiewicz.

He has a quick, ready wit — yet he thinks and acts and plays games with deliberateness. He plunges joyfully into the frenetic pace of the backgammon circuit — yet he often longs for the tranquillity of academia. When hunched over a backgammon board, he screens everything from his mind except the four quadrants of the board and the checkers upon them — yet he is a showman who loves playing to an audience. He is too busy to have a romantic attachment — yet women find him enormously appealing. (“Watching Paul play is a sexual experience,” says Fran Goldfarb, a top-ranked woman player from New York.) He is fiercely independent — yet he craves attention and recognition. He has the mind of a Phi Beta Kappa and National Science Foundation Fellow — yet he often behaves like a Katzenjammer Kid.

Paul Magriel established himself as backgammon’s foremost theoretician in 1976 when he published a work called, simply, Backgammon, which quickly became to the game what Paul Samuelson’s Economics became to economics in the 1950s — the authoritative text on the subject. In June 1977 Magriel’s backgammon columns began appearing every Thursday in The New York Times. “That’s one of the few structured things in my life,” he says. “Every Monday that deadline comes around, and I’m never ahead.”

Typically, Magriel deprecates his book. “It’s gotten to the point where I can’t even look at it because I see all its glaring deficiencies,” he says.

To overcome these deficiencies, he is planning a series of nine new books — on the doubling cube, on the attack game, on openings, on prime vs. prime, and so forth — each building on the ground broken in his initial work. He is also writing a book of annotated games, based upon a highly involved match he lost last fall to Bill Robertie of Boston, and he is getting a book of backgammon problems ready for the press.

There are other books Magriel wants to write — on compulsive gambling, on the nature of games, on the foundations of probability. At the same time, he has been commuting to Pittsburgh to work with Dr. Hans Berliner, an artificial-intelligence specialist at Carnegie-Mellon University, on the development of a computer backgammon game, which is more advanced than any now available. He is studying such apparently divergent subjects as the philosophy of science and the Japanese game of Go, which he perceives as related parts of the quest for meaning and order. And he is continuing his studies of chess. When he was 19, he was New York State junior chess champion but gave up playing seriously when he went to college; mastering the game as thoroughly as he wanted would have taken up all of his time.

“There is all this material,” Magriel says, gesturing hopelessly at the stacks of notes and unfinished manuscripts littering his apartment. “I’m getting older and older, and there are a million things I haven’t gotten done.”

A couple of days after their meeting in New York, Prince Nawaf invited Magriel to his $2,000-a-day suite at the Waldorf-Astoria.

“I want you to come to Saudi Arabia and teach me backgammon,” the prince said.

“When?”

“Right away.”

Prince Nawaf was not the first wealthy and famous person to seek instruction from Magriel. He has given backgammon lessons to the likes of Hugh Hefner and Lucille Ball, as well as to many regulars on the tournament circuit.

“There may be some question in some people’s minds about who the best backgammon player in the world is,” says one of his pupils, a world-class player himself. “But there is no question in anybody’s mind about who the best teacher is. He’s Paul Magriel.” Says another expert, “He’s very patient with stupid people. He not only knows what the right move is, he can explain the reason why, which many professionals are unable to do. And being an ex-college professor, he knows how to explain things over and over again.”

At the Waldorf-Astoria that day in November 1977, Magriel told Prince Nawaf that other commitments would prevent his coming to Saudi Arabia before February. One of these was the world backgammon championships on Paradise Island in the Bahamas in January. The world title had always eluded him, and he was determined to win it. Which he did, defeating Kent Goulding of Washington, D.C. in a hard-fought semifinal match and trouncing Kal Robinson of Los Angeles in the finals. Magriel’s winnings at Paradise Island totaled $70,000.

Magriel's only regular chore is to write a Thursday backgammon column for The New York Times.

“I feel ambivalent about the title ‘world champion,‘ ” Magriel says. “It’s only one major tournament among others.” He compares the relatively short Paradise Island tournament, which culminated in a 25-point final that took about three hours to play, to the three months it took Anatoly Karpov to defeat Viktor Korchnoi for the world chess championship, and the hundreds of deals teams must play in the world bridge championships. He would prefer the finals of the European Backgammon Championship, which he will defend in Monte Carlo in July, to be decided by a 100-point match so that the luck factor would be lessened. Nevertheless, Magriel doesn’t doubt that he deserves the title. “I’m always top-seeded,” he says, “because I have a better track record than anybody else.”

So in February of last year, off he went to Saudi Arabia to polish up the prince’s game. The nightly lessons began in Nawaf’s palace in Jiddah, continued in his palace in Riyadh, and ended a month later in his mansion in London. Even the four-day falconing excursion didn’t interrupt the lessons. After the day’s hunt and the sumptuous dinners — eschewing the cutlery set out for him, Magriel ate with his fingers in the traditional manner — the prince and the professor took out the backgammon board. In the quiet desert night, the rattle of the dice permeated the royal encampment like the laughter of a djinn.

A strange place, the Arabian desert, for Magriel to have found himself in his 32nd year. Yet his life is a cumulation of paradoxes — not unlike those presented in the illusionistic Vasarely prints that hang in his apartment.

Paul David Magriel was born in Manhattan on July 1, 1946. His father was a prominent New York art dealer, his mother a graduate of the MIT School of Architecture. Among the guests at parties they gave in their Upper East Side apartment and at their summer home in Well-fleet on Cape Cod were Arthur Schlesinger Sr., James Agee, Walker Evans, Franz Kline, Eero Saarinen. Magriel remembers hearing Edmund Wilson arguing with stentorian gusto at his parents’ apartment, and at the Cape, Magriel used to go deep-sea fishing with Norman Mailer. He also often accompanied his parents on their tours of the museums and private art collections of Europe. Last summer he met French backgammon enthusiast Marquis Guy d’Arcangues at the European Championships in Monte Carlo. After they had talked a while, Magriel discovered it was the Marquis’ chateau that rose so near the house in the South of France that his parents used to rent when he was a child.

When Magriel reached school age, his parents sent him to the highly regarded Dalton School in Manhattan and later to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. After Exeter, Magriel entered the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at NYU, completing the four-year curriculum in three. From there he went to Princeton to do graduate work under William Feller, whom he considered the country’s foremost authority on mathematical probability. Magriel’s career seemed clearly mapped out: he would become an academician, a scholar, the author of erudite mathematical papers.

But something happened. Games got in the way.

Back when Magriel was five, his mother taught him chess, and those lessons opened the whole world of games and gaming for him. Whereas the shy boy found life confusing, even frightening — full of weighty and ambiguous matters debated by adults — games were another matter. Games were neatly bound by clearly delineated rules; they had a well-defined right and wrong. What’s more, he was good at them.

The secure feeling engendered by games has never left Magriel. Two years ago he told Susan Silver of the Soho Weekly News, “I am addicted to games in general. Games are controlled violence. You take out your frustrations and hostilities over a backgammon set. . .. In games, you know what’s right and wrong, legal and illegal; whereas in life, you don’t.”

While at Dalton, Magriel would gather his second- and third-grade classmates in his apartment to play nickel-and-dime poker after school. They played draw, stud and a complicated high-low split game they called “plodiv,” during a hand of which Magriel remembers literally losing the shirt off his back. Then he and his best friend acquired a roulette wheel; they secretly ran it until one of their schoolmates lost the astronomical sum of $5 and went crying home to mother. The parents busted up the game.

“My friend and I were smart enough to realize that the house had an edge,” Magriel says. “None of the other kids believed it because it seemed like the house was a fixed target they could take shots at. So somehow, even at that very tender age, I in some sense understood the concept of vig — that all-important concept, which many primitive societies have not understood at all.”

Indeed, it was Magriel’s youthful interest in gambling concepts like vigorish, odds and parlays that led to his interest in mathematics. “My development is almost an exact parallel of how historically the theory of probability began,” he says with a certain perverse pride. “Historically, there were gamblers, and to try to figure out the odds, they went to mathematicians like Pascal and Pierre de Fermat. As a kid I used to play with dice, trying to figure out various permutations, and then when I opened up some math books, I discovered the problems I had worked on so hard could easily be solved mathematically. At Exeter I decided I wanted to find out more about probability, which is what I eventually specialized in at Princeton.”

Two important events occurred while Magriel was at Princeton. He married his longtime friend, Renée Cooper, a doctoral candidate in medieval literature at NYU, and he discovered backgammon. After a year of graduate work, he left Princeton in 1968 to take a teaching position in the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark, which was across the Hudson River from New York’s May-fair Club, where probably the best back-gammon in the country was then being played.

“It was a rough-and-tumble club in those days,” Magriel says, “but the atmosphere facilitated the exchange of information. I learned a lot from my opponents’ insults.”

Backgammon cast a spell over Magriel. It was mathematical, yet it incorporated the elegant strategies and tactics of chess. It was a game of skill, yet the skillful player was always gambling with the randomness of the dice. And, for Magriel, it was maddeningly hypnotic. “It got to the point,” he says, “where I’d play in games at the Mayfair all night long, then teach my 9 o’clock classes, and then go home and sleep. Then I’d get up and go over there and play all night again.”

The Magriels weren’t well-off, and it wasn’t easy for Paul to come up with enough money to get involved in a paying game. But after several months of scrimping and skipping movies, he got together a small stake and went off to the Mayfair one night to take on all comers. He returned to their tiny apartment at dawn, richer by $300.

“After that first night, I begged him not to go back,” says Renée, who had little interest in either games or gambling. ” ‘Listen,‘ I said. ‘You won, but you’re never going to win again. Let’s just take the money and spend it.‘ But Paul was sure he could keep on winning. He just kept going back, and pretty soon we kind of lost our perspective as far as money went. It didn’t seem to matter anymore. Money was just points in a game.”

On weekends, Magriel would sometimes whiz off to tournaments in the Caribbean or Europe and get back in time (usually) for his Monday morning classes. He and his wife got divorced after 2½ years of marriage, and he reduced his teaching load to part time. Backgammon was becoming more exciting, more challenging and more rewarding — intellectually, emotionally and financially — than teaching math. In 1975 he quit teaching altogether, and the world of backgammon made him its star.

“Backgammon is very similar to chess,” Magriel is saying. “It is deceptively easy to learn, but in reality it is a profound game of position and strategy. The whole thrust of my game is using all of my pieces effectively and, at the same time, restricting my opponent’s mobility.”

The master is at the moment barefoot, wearing a baggy sweat shirt and patched jeans. He is lying on a hotel-room bed, his head propped up on an elbow. It is the afternoon of his challenge match in the first Magriel Cup Tournament at Mexico City’s Chapultepec Golf Club. Stacks of papers have somehow managed to spread themselves across the room. On top of one of them is an unfinished draft of a backgammon column, due at the Times the following day. A half-eaten apple crowns a bowl of fruit on the dresser, and a backgammon board, the pieces in disarray, is on the table under the lace-curtained window. Open facedown on the bedside table is a thick volume, Lawrence M. Friedman’s A History of American Law.

“Then there’s this personal thing,” Magriel says. “I’m always at war with luck and disorder. I’m always trying to impose my will over the randomness of the dice, over what seemingly has no structure. I may be sounding sort of melodramatic, but what I’m trying to do in backgammon is create order out of chaos. I guess in a psychological sense, I’m trying to make sense out of the world. People think there’s so much luck in backgammon.” Magriel gets up and begins to dress for the match he will play that evening. “But that’s very unfair. They think there’s not that much to the game. That’s totally false. Backgammon is much, much more difficult, much more complex, much deeper than anybody can imagine. The dice create this surface chaos, which is always riling things up, but there are patterns underneath the surface that involve advanced, beautiful, non-obvious, non-trivial ideas. It’s my job to uncover these patterns.”

Downstairs, heading for a cab outside the hotel, wearing a fur coat that was a present from a female admirer, he says, “I was very, very lucky. I stumbled on backgammon, and it happened to be exactly right for the kind of talents I have.”

For three days there had been nearly as many ways of getting some action at the Chapultepec Golf Club as in a Las Vegas casino. The backgammon crowd was in town, and wherever it gathers, there’s always action. While first prize in the tournament itself was a modest $4,350, the winner had a chance for an additional $10,000. All he had to do was beat Magriel in a 25-point match. If Magriel won, he got the $10,000.

In the club’s spacious, glass-walled lounge overlooking. . .well, overlooking something — in the backgammon world it always seems to be night, and even if it isn’t, who would notice what the lounge overlooks anyway? In the lounge, at any rate, games of all sorts were going on everywhere, constantly. In an alcove, the co-owner of a Los Angeles bridge and backgammon club was improving his gin game at the expense of a backgammon pro from Las Vegas. A couple of bridge foursomes were playing in a corner, and elsewhere, at one time or another, there were poker, dice, dominoes, pinochle and every sort of gin game. But mainly there was backgammon, not just the tournament matches in the ballroom, but the money games in the lounge at $10, $25, $50, even $100 a point.

Former world champion Baron Vernon Ball was there, playing in a $50 chouette (a popular and expensive form of backgammon play, in which more than two may participate) with a couple of friends from St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. Some of the best Mexican players were on hand. And so was a small band of unsavory young Mexican con men, who picked up games from whomever they could at whatever price they could get — without worrying much about paying up if they lost.

One hundred dollars a point may not sound like very heavy gambling, compared, say, to high-stakes poker, until one understands a few things about backgammon. On average, it takes a good player from five to 10 minutes to move all 15 of his men successfully around the board and bear them off for a victory. That’s $100 right there. However, if he develops his game in such a way as to move all his men off while preventing his opponent from bearing off even a single man, he’s won a gammon, which gives him a double score. That’s $200. And that’s only the beginning. There is also that small, unprepossessing object called the doubling cube.

During the course of a game, either player, when he feels he has a sufficient advantage, may turn the cube to 2, thereby doubling the original stake. The doublet’s opponent has the option of passing, in which case he concedes the game at the original stake, or of accepting, in which case the game continues, and, very importantly, the doubling cube comes into his sole possession. Should he later gain the advantage, he may turn the cube to 4, thereby doubling the stake once again. Now it’s the original doubler’s turn to decide whether to pass and concede two points or accept the cube and continue the game at the 4 level. And so on, though in practice the cube rarely gets up as high as 8. Obviously, at $100 a point, losing an eight-point game or, worse, getting gammoned in an eight-point game can be pretty expensive. “Doubling is one of the most important and exacting aspects of backgammon,” Magriel has written. “The doubling cube holds the key to being a winner or a loser.”

While the tournament proper was going on, Magriel could be seen bounding from one game to another with a glass of soda in his hand (he doesn’t drink alcohol, nor does he smoke), kibitzing, talking to old friends, giving advice, joking and not infrequently sitting down for a few games.

Then he had to face the winner, who turned out to be not one of the early favorites, but 13th-seeded Russell Samuels, a U.S. citizen who lives in Cuernavaca. Samuels would now have his shot against Magriel for $10,000.

“Paul certainly has some slight technical edge on me,” Samuels said as he waited for Magriel. “But I’m not particularly nervous. The money doesn’t come out of my pocket.”

But that was before Magriel made his entrance and sat down at the backgammon table opposite him. The champion’s appearance was nothing if not calculated to unnerve Samuels. The boyish person who during the previous three nights had relished playing casual money games had been replaced by a much grimmer individual. Magriel now wore a dark blue pinstriped suit, with a red silk handkerchief carefully squared in the breast pocket. His mouth was set and his face expressionless. The dark glasses he always dons for match play transformed his face into something like a machine. Paul Magriel had become X-22.

Samuels tried conversing with the machine to break the tension. Magriel would have none of it. He thrives on tension. He had been there many times before, while Samuels hadn’t. Magriel might sometimes throw away his edge in money games. (“He has no notion of pigeon-handling,” says Los Angeles pro Gaby Horowitz. “He’d be rich if he did.” Magriel himself concedes, “My approach has always been motivated intellectually more than financially — to my detriment.”) But in a match with a couple of hundred people around the table rooting for the local underdog from Cuernavaca, Magriel’s reputation was on the line. He would do everything not only to minimize the element of luck, but also to intimidate his opponent.

Though he started the match slowly, losing the first three games, Magriel soon built up an imposing 15–8 lead. He never said a word, never acknowledged the presence of anyone or anything outside of the games developing before him on the board.

Before this monolith, Samuels certainly showed signs of nervousness. He smoked incessantly. Two half-empty packs of Marlboros, a mound of match-books, a rapidly filling ashtray, a glass of Coca-Cola, a score sheet and a pen were in front of him. Magriel’s side of the table was bare. Occasionally he would nudge the checkers so they formed absolutely straight rows on the board; as he thought about a move, he would square the dice perpendicularly against the bar separating the two sides of the board, as though he wanted the board to reflect the harmony and order he was trying to find in the fall of the dice.

Samuels won a quick game, making the score 15–9. In the next game, after the doubling cube had gone up to 4, Magriel developed a position that made him the heavy favorite. Samuels was blocked behind a five-point prime — that is, five consecutive spaces owned by Magriel, because he had two men on each of them. Only a 6-1 roll, a 17-to-1 shot, could save the game for Samuels and prevent Magriel from gaining an almost insurmountable 19-9 lead. Samuels shook his dice, tipped his cup. The dice spun out onto the board, 6-1!

Samuels was alive. He leaped the prime and hit Magriel’s open man behind it, sending the man back to begin the route around the board over again. The game had completely turned around. When it ended, the score of the match was Magriel 15, Samuels 13 instead of 19–9. Magriel seemed undisturbed.

An hour later the score was 22–22. Magriel then engineered a deft trap play that demonstrated why he is the world champion. He was working for a gammon, a double score. But Samuels managed to escape, and Magriel had to be satisfied with one point. Score: Magriel 23, Samuels 22. Magriel was stony-faced. Samuels was rubbing the sweat from his palms on his pants legs.

In the next game Samuels developed a very favorable position and doubled. Magriel deliberated a long time. He could have passed, conceding one point to Samuels, but to the surprise of everyone around the table, he accepted. Afterward he insisted that it had been a reasonable decision. Samuels rolled a 2 to hit one of Magriel’s men (the odds against his doing it had been 2 to 1), and now Magriel needed a 6-3, 6-5 or 6-6 roll to turn matters around. At the very least, he needed a 6 on one of his dice to stay in the game.

As he shook the cup violently, Magriel’s tongue protruded from a corner of his mouth. He was biting his tongue. Whatever he might say later, he most definitely cared about this roll. He wanted a 6. He was rooting for a 6. The dice fell on the board. No 6.

Samuels’ position kept improving. Now he had all his men in his home board and could start bearing them off. Now he was bearing them off. And now Magriel needed to race his back men around the board to avoid a gammon, a double game which, because the doubling cube was at 2, would give Samuels four points and the match, 26–23.

With one man left to bring into his home board in order to start bearing off, Magriel rolled a horrible 1-1. Samuels bore off two more men. He had only two men left on his No. 1 point and would win the game on his next roll. However, Magriel was still in the match so long as he didn’t roll 1-1, 2-1, 3-1 or 3-2. Any other roll — 29 of 36 possibilities in all — would allow Magriel to bring his last man into his home board and bear one man off. He was slightly better than a 4-to-1 favorite not to get gammoned.

Magriel shook his cup and let the dice fall. They bounced crazily around the board and came to a stop. Magriel stared. Samuels stared.

Double aces!

A pause. Then a roar from the crowd. Samuels leaped up and shook Magriel’s hand. He had beaten the world champion. The crowd swirled around him. They carried him off to the bar to celebrate.

Magriel sat in his chair in the now empty room, staring in dismay at the double aces. He could not believe what had happened. Resting on the felt surface of the backgammon board, the dice seemed to be mocking him. Magriel shook his head. There they still were. Double aces. Snake eyes. On this night, the enemy, the agent of disorder and chaos, had triumphed.