|

| Book Transcription |

|

|

so ought we to arrange our affairs

according to the throws we get,

as reason shall best

declare.” —Plato

The Story Of Backgammon

The recent tremendous growth in the popularity of Backgammon as a social diversion is doubtless due to the fact that it is a game so thoroughly attuned to the modern spirit of youth.

Backgammon is probably both the oldest and the most youthful game in the world. For, even though it may have been the familiar pastime of Pharaohs in Egypt and Kings of Ur, in its very essence, Backgammon answers the demands of our times for unfettered, fast-moving, exciting amusement.

Of course it is only by our Twentieth Century innovations that this pastime of so many leisurely centuries has been revamped into the most spirited of up-to-date entertainments.

First came the variation of optional doubles, not only to increase the scientific interest of the game but to accelerate its pace to a speed compatible with the tenseness of our present-day life.

A double promptly offered, quickly rejected! Off with the old set-up, on with the new! That is the modern Backgammon, where ten games may be played while before one dragged to a tedious foregone conclusion.

Then came the second feature of Chouette completely to metamorphose the circumscribed two-handed pastime, over which of a winter’s evening our grandfathers and grandmothers mildly contended beside the fire.

With the introduction of Chouette, Backgammon suddenly found itself a most fashionable and up-to-date diversion permitting the entertainment of any odd or even number of people from two to five or six.

More than anything, this feature of Chouette is responsible for the outstanding social popularity of Backgammon. The flexibility of Chouette, with its constant changing of partners and the freedom it allows for players to drop in and out of a game with entire informality, is a distinctive attraction. This phase of the game is likewise a real blessing to the hostess, who, entertaining at Backgammon, is independent of the tardy or recalcitrant guest.

Another feature of Backgammon particularly pleasing to our modern spirit is the fact that it is not too exacting. A successful game of Backgammon requires alertness, intelligence, quickness, but it does not necessitate concentration, or like Chess or Bridge, love or the stock market, demand the whole man.

Undoubtedly the vogue of Backgammon is sweeping the country. Every day more and more players are capitulating to the undeniable charm of this high-speed, but really scientific, gambling game. More and more it is becoming a question not of “Do you play Backgammon?” but “How well do you play Backgammon?”

Certainly the story of Backgammon goes back to prehistoric times and in popularity the game seems to have outlasted all other ancient forms of amusement. There are many conflicting accounts regarding its origin, its birthplace being claimed by more communities than claim Homer’s.

The Japanese lay serious claim to the invention of Backgammon. The ancient Greeks certainly had a similar game known as Abacus. A Sanscrit quotation reads:

“Thus Kala and Kali casting day and night with a pair of dice play with human pieces on the board of the world.”

Which sounds very like our modern Backgammon on a large scale.

In the tomb of Tutankhamen were found a gaming board, with sets of men and some dice. And similar discoveries have revealed that a game played with draughtsmen and dice was known in Ur of the Chaldees more than five thousand years ago.

Thus, every now and then something turns up to set the story of the game back a few thousand years or so and make it more and more apparent that its origin will never be traced.

As a matter of fact, Backgammon probably did not begin as an invention but as an evolution. Doubtless the men were originally mere counters, perhaps round stones moved on a lined board to keep track of the throws of dice. After a time skill began to mingle with chance and to dictate the moves of the counters.

The source of our own title for this widely popular game is disputed by historians. Some ascribe it to the Welsh bach, little, cammum, battle, while others trace its source to the Saxon baec, back, and gamen, game, i.e., a game in which the men may be set back.

That Backgammon was played by the ancient Saxons and Welsh is indisputable. And it appears equally certain that both acquired it from the ludus duodecim scriptorum or twelve-line game of the Romans. The Roman Legions must have spread their beloved twelve-line game over the greater part of Europe, for everywhere that Roman eagles perched some form of the game became popular.

In most European countries to-day, Backgammon is played under the French designation of Tric Trac, but the Italians accord it more honor by denominating it Tavola Reale, the royal table. Our earliest accounts of the game, very nearly as we now play it, come from the England of Chaucer’s time when it was known as Tables.

Spenser refers to Tables in his Faerie Queen. Bacon recommends it as a good game. Addison, Dryden, and other writers of their day mention it as a gentlemanly pastime; one even going so far as to prescribe a bout at Tables as an “anodyne to the gout, the rheumatism, the azure devils, or the yellow spleen.”

And here is another old writer who, while indulging in unstinted praise of Backgammon, pauses to take a nasty dig at the great-grandfather of our own Contract:

“From time immemorial Backgammon has held the foremost position among the elite of popular games. It has ever been a game for the higher classes and has never been vulgarized or defiled by uneducated people. In that respect it differs from Whist which has seen its day in the servants’ hall but will ever be shunned in higher circles.”

Backgammon has always been a famous game with the clergy. When Sir Roger de Coverly was “wishful,” as he wrote, to obtain from the university “a chaplain of pretty learning and urbanity” he made it a condition that the candidate should play Backgammon.

In Scotland, also, the game seems to have been in repute among the gentry, for history tells us that James I spent the evening previous to his murder playing at Chess and Tables with the ladies and gentlemen of his court.

It is also recorded that in 1479 when the Duke of Albany, the brother of James III, was confined in Edinborough Castle, he invited the Captain of the Guard to sup with him, and the evening was spent “in much hilarity, with many libations and play at tables.”

In the morning the royal prisoner had disappeared and his gaoler-guest lay “a blackened corpse upon the hearth” — Backgammoned beyond a doubt.

How To Use the Book

I have sought to keep this book as short as possible while making it really instructive and comprehensive for the student who wishes to learn the new Backgammon.

The method of exposition adopted is the one which I have used with some success in teaching the game. First the indispensable mechanics are set forth. Then comes Part Two with a comprehensive outline of the general strategy of Backgammon. Parts Three and Four progress to more advanced strategy and the treatment of specific situations. The last part of the book contains the rules and some additional advice to advanced players with special stress on psychology and doubling.

It would be best for the novice at Backgammon to follow the sequence of instruction exactly as embodied in the following pages, mastering one subject before proceeding to the next. At the same time, the arrangement is such that the player of any degree of skill can take up the book, and beginning at the point to which he has already progressed, carry on his study of the game in a logical sequence. For example, a player with a thorough knowledge of the mechanics of Backgammon but not well posted in its strategies can completely omit Part One, and still be assured that he will miss nothing of value to himself.

Also it will be noted that each subject is covered and indexed under a sub-heading so that the book may serve all classes of players for ready reference even during an actual game.

PART I

The Mechanics of Backgammon

The Board and Its Set-up

In starting out to play Backgammon, the first thing to consider is your board. Nothing adds more to the pleasure of the game than a roomy, properly made board.

The ideal board is of solid construction, like the top of a bridge table, and is furnished with the same type of folding legs. However, a smaller folding board, which may be used on any table, is very satisfactory provided its dimensions are no less than 20″ by 18″. A board of lesser size which necessitates the use of too small men and dice causes the players to feel cramped and restricted.

The type of board above all to be avoided is the old-fashioned combination Checker and Backgammon board with the high, narrow railing. Whatever the dimensions of the board you select, be sure to see that the bar and railing are broad and flat. The railing should be high enough to keep the dice and men inside, but not so high as to prevent the partners at Chouette from seeing all points of the table.

As will be later shown, quite a number of people can take part in the modern game of Backgammon. But the playing proper can be done by only two contestants. Each player is provided with a dice box, two dice, and fifteen men. The opposing men are of different colors, Black and White, the opponents being distinguished by the color of the men with which they play.

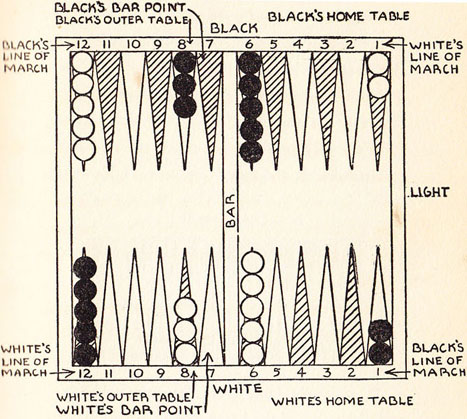

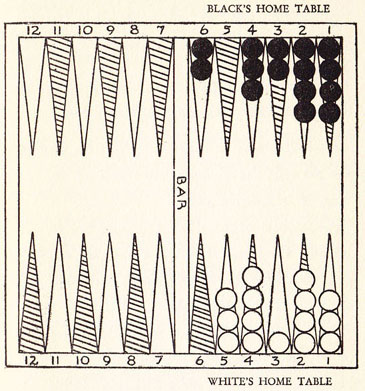

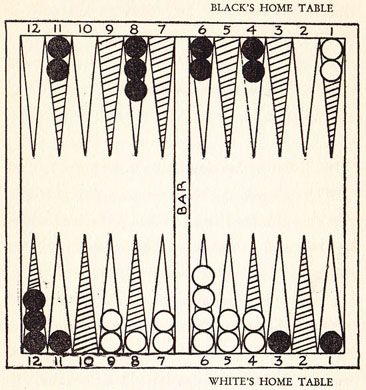

As shown in Diagram I, a Backgammon board consists of twenty-four points of two alternating colors.

Diagram I

The board is divided into four tables. Black and White each have an inner and outer table, the points of the inner or home table being known by numbers from one to six, each number corresponding to one of the faces of a die.*

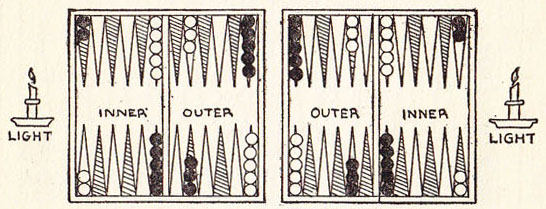

The inner tables may be set up either as shown above or on the other side. An ancient custom Which is still generally followed is to place the inner tables “nearest the light.” Diagram II illustrates this.

Diagram II

Dividing the inner from the outer tables is a raised portion of the board called the bar, next to which will be noted an important point known as the Bar Point.

At the outset of the game the men are set up on the various points in the positions indicated. It will be noted that the White men on any point have exactly the corresponding number of Black men placed opposite them. Each contestant sits on his own side of the board and plays from that position.

Object of the Game

The object of the game is for a player to move all his men into his inner table and then throw or bear them off from the board before his adversary can accomplish the same end, all of a player’s moving and bearing off being made in accordance with numbers indicated by the successive casts of his dice.

Line of March

A player’s line of march is from his opponent’s inner to his outer table, thence across to his own outer table, into his own inner table, and finally (when all his own men have reached his inner table) off the board. As indicated by the arrows in the first diagram, when the men are set up with the inner tables as illustrated, the men in Black’s position move clockwise, while those in White’s move counter-clockwise. Thus the opposing men are continually meeting and passing each other.

The Play

A game is started by each contestant throwing one die. In case of a tie, the players throw again until one or the other throws a higher number. The player with the higher cast makes the first move for which he must adopt both the numbers thrown. For example, if White’s cast is a five and Black’s a two, White makes the first move, using the five and two as his numbers.

After the first play each contestant in turn throws two dice from his own cup into the portion of the board at his right and makes his moves accordingly. A player can move a man as many points as there are spots on the face of the thrown dice, counting from but not including the point on which the man starts. A different man can be moved for each die, or the whole throw can be taken with one man in two distinct moves, corresponding exactly to the number of spots on each of the dice.

A move must always be made if possible. When all possible moves are blocked, the player loses his throw. If, however, he can play one but not both of his numbers, he must play the higher. Any number of men of the same color may be placed on one point.

Blocked Points

A move may be made to any point unless that point is occupied or blocked by two or more of the enemy’s men. For example, on White’s opening play of five and two, he could not move one of his men from Black’s inner table on the five throw because the point to which this move would carry him is blocked. Nor could White take the whole throw of seven with one man, because while he could use the two as the first move to a free point, the second move of five with the same man would land him on another of Black’s blocked points. It must be remembered not only that a man is forbidden to stop on a point blocked by the opposite color, but that he can never even use it as a temporary resting place in essaying a double move. A blocked point may, however, be jumped. For example, had White’s opening throw been a six and Black’s a two, White using these two numbers for his first play could have moved a man from Black’s inner table, jumping Black’s first blockade on the six move and his second on the two.

Doublets

A throw of doublets, that is of two dice each showing the same number of spots, entitles the player to four moves instead of two. For instance, if a player throws double threes, he has his choice of moving one man twelve points, two men six points, four men three points, or one man nine points and a second man three points. In short the move may be taken in any way so long as the units of three are preserved and no adversely blocked point is touched.

Establishing a Point

A player moving so as to place two or more men on the same point is said to establish that point.

Blots

Whenever a player leaves a single man upon a point that man becomes a blot. If an adversary can move to the same point either by a single or the combined numbers of his throw he may, if desired, hit or take up the blot. A player is not obliged to hit an enemy blot; he may exercise his judgment in doing so. But if in moving one or more of his men he stops or rests upon a point occupied by an enemy blot, that blot is automatically hit. When a blot is hit the man is removed from the board and placed upon the bar.

Reentering

A player can only reenter a man who has been hit and retired to the bar by throwing a number corresponding to the number of an unblocked point in the adversary’s home table. For the purpose of reentering, combined numbers of the dice cannot be used. For example, a player could not utilize a throw of three and one to enter on his opponent’s Four Point.

After a blot has been taken up and the man has been reentered, he must again work his way around the line of march to his home table. As long as the player has a man on the bar, he cannot move any other man. Thus, if every point on White’s table were blocked and Black had a man on the bar, it would be useless for Black even to throw his dice until a break occurred in White’s blockade. In the meantime, however, White would go right on throwing and making his moves.

A man on the bar can enter the opponent’s table and take up an adverse blot at the same time.

Naturally, a man can always be entered on a point occupied by one or more men of his own color.

Bearing or Throwing Off

When either player has succeeded in bringing all of his men into his home table, he may immediately begin throwing or bearing them off from the board. So long as all of his men are across the bar, the throwing-off process may commence irrespective of which parts of his home table are occupied by his own or his adversary’s men.

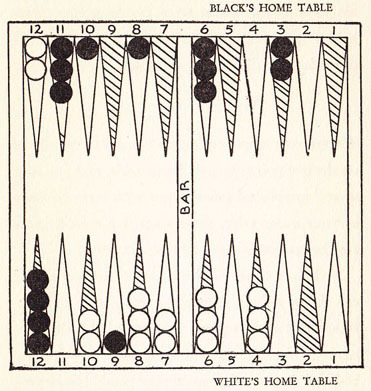

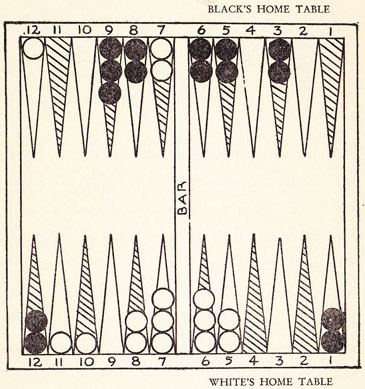

A player throws off his men two (or in the case of doublets, four) at a time according to the throws of his dice and provided he has men on the points corresponding to the numbers thrown. If there are no men on a point corresponding to a number thrown, other men must be moved toward the Ace Point. When it is impossible to move because of a large number thrown, such as a six, when there are no men on the Six Point, a man must be taken off from the next nearest point. Diagram III illustrates this.

Diagram III

Throwing Off

In Diagram III both Black and White are ready to throw off.

If White throws six-five, he would bear off two men from his Five Point. One he naturally takes off for the throw of five; the other because it is impossible to move up for the six throw.

In Black’s case, with men on the Six Point and none on the Five, should he throw six-five, he could bear off only one man from the Six Point. The other would have to be moved to the Ace Point.

It is not obligatory for a player to throw off a man if he prefers to move, but he is compelled to do one or the other.

When a player has started to bear his men, he is sometimes forced to leave a blot which may be hit. Should this happen, he would have to stop throwing off until he had succeeded in reentering his man and bringing him around the board to his home table.

Gammons and Backgammons

The first player to throw off all of his men wins the game. If the adversary has taken off any of his men, it is a single game.

Gammons occur when the loser has failed to take off any men before the winner has cleared all of his from the board. A Gammon is a double game, doubling the original stake.

Backgammon is scored when the loser has not only failed to remove any of his men from his board but has one or more remaining in his opponent’s inner table or on the bar. A Backgammon triples the original stake.

When playing the modern system of doubling and redoubling, Gamrnons are always counted, but some players do not retain the feature of Backgammon.

Optional Doubles

Gammons and Backgammons, both features of the old game, are mechanical doubles. But the type of double to which much of the recent tremendous development in the popularity of the game may be ascribed is entirely optional. As they may be offered, accepted, or rejected at the discretion of the players, it may readily be seen that these modern doubles add greatly to the scientific element of the game.

This system of optional doubling operates as follows:

After a game has started, either player immediately before any cast of his dice may say, “I double.”

Thereupon the adversary has the privilege of saying, “I resign,” which means that he is willing to surrender the game and pay the original stake; or he may say, “I accept,” in which case the game proceeds at a double stake.

After a player has accepted a double, he gains the sole right to make the second double and may do so at any time just before he throws his dice. When such a redouble is offered, the initial doubler may resign and pay the doubled stake, or he may accept and continue the game at a redoubled stake. In accepting the double, he, in turn, acquires the sole right to offer the next double, and so on.

During the course of a game this doubling and redoubling may continue indefinitely, the privilege of a new double always resting with the player who has accepted the last. Thus it is obvious that even a modest original stake can be increased to an enormous proportion by repeated doubles. While, however, any number of doubles are permissible, in actual games they seldom go beyond three or four. Among conservative players more than one double and redouble is rare.

As a curb to reckless doubling and redoubling, it must be remembered that the possibility of a Gammon or Backgammon may, at the end of the game, automatically double or triple the final stake. To illustrate, suppose a stake starting at I has been doubled to 2 and redoubled to 4, and the game ends in a Gammon, the final loss would he 8 or eight times the original stake. A Backgammon would, under the same circumstances, increase the original stake to 12. As a matter of interest it might be noted that five doubles would increase the original stake of 1 to 32, while ten doubles would increase it to 1,024.

Automatic Doubles

A still more recent development of Backgammon is an additional form of doubling called the automatic double. The automatic double doubles the original stake if, in casting for the first move the players throw matching dice and have to throw again. A second tie automatically redoubles the doubled stake, and so on. As there is no limit to the ties which may occur, and as this automatic double, unlike the optional double, detracts from the science of the game, most players set a limit of three on their automatic double, while many of the more conservative omit them entirely.

Scoring by Matches

In order to regulate and simplify all the doubling and the matter of credits and losses, New York society has invented a very simple device of matches. A bowl of ordinary parlor matches is put somewhere near the players. The matches in the bowl belong to nobody. They are, so to speak, community matches. At the outset of a game one match is placed upon the bar. If a double occurs (automatic or optional) another match is taken from the bowl and placed upon the bar; a third double would mean four matches on the bar, a fourth eight, and so on.

Once a game is over, the winner takes all the matches on the bar and they become his matches. Never, at any time, can both players have matches before them, because there can be only one winner in a two-handed game.

If you, playing White, have six matches before you, and lose a doubled game, or two matches, you return two matches to the bowl, leaving four matches net. If you then lose a four-match game, all your matches are returned to the bowl.

Under no circumstances should you hand any of your matches to Black, as the account would then become confused. The only matches a winner can receive are from the bar. To start each new game one match is taken out of the bowl and placed upon the bar.

Scoring with a Doubling Cube

Many players, especially in Chouette, prefer to keep track of their doubles and the current stake with a device known as a doubling cube.

This is a cube, like a large die, numbered on its six faces as follows: 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64.

For convenience, at the beginning of the game, the cube is usually placed with the 64 face up.

As soon as a double is established (automatic or optional) the 2 is turned up. At a second double, the cube is turned to 4, and so on. As a further tally, the cube should be placed before the player who has the privilege of the next double.

Chouette

While the actual physical play is limited to two persons, modern Backgammon permits three, four, five, or even six people to participate in a game. This very popular and attractive innovation has been made possible by the addition of the feature known as Chouette.

To clarify the operation of Chouette, it will first be described as played by three players. Each player commences by throwing one die. The one who throws the highest numbered die is said to be “in the box,” that is, he must play the game against the other two. If he loses the game he loses the amount of the stake to each of the other players, or if he wins, he wins the amount of the stake from each of the others. The one who has thrown the second highest number takes his place at the table and, assisted by suggestions from the third player, opposes the man in the box.

The inactive player is allowed no actual part in throwing the dice or making the moves, but he has, throughout the game, unlimited powers in rendering advice to his partner, calling his attention to advantageous moves, and warning him of possible dangers. And while only the active partner has the power to offer, accept, or reject a double, when questions arise of doing so, he is expected to consult with his inactive partner.

In case of a difference of opinion between partners concerning questions either of plays or doubles, the decision of the active partner must be final. When, however, partners disagree about accepting or declining a double offered by the player in the box, it is permissible and entirely reasonable that the partner who wishes to resign may do so. In such an event he forfeits to his partner the amount of the stake at the moment and retires. The partner who has accepted the double continues the game, assuming the liability of any further losses or, in case of winning, taking all the profits.

If the player in the box wins a game, he continues in the box. His active opponent becomes the inactive partner, the third player taking his place at the board and opposing the player in the box. As long as the player in the box continues to win, the game proceeds in the same way, the opposing players becoming alternately active and inactive partners. At once, when the player in the box loses a game he retires to the position of an inactive partner, the player who has defeated him taking his place in the box, to be opposed by the third player.

When Chouette is played by four or more it proceeds in the same manner as indicated for three players. All players having thrown below the two highest numbers become inactive partners of the player opposing the man in the box; all having the same interest in the game, with equal rights to give advice and offer suggestions to the active player. According to the order of their original casts, these inactive partners move toward and into the two active positions in the subsequent games.

With a large group, it is a courtesy at Chouette for the casters to call out their numbers.

In starting a game of Chouette, when the players throwing the highest numbers tie, it is customary for everyone to throw again. For instance, if two or more candidates threw sixes, all players would have a second throw. But when the tie occurs only among the lower throws, the two highest players take their place at the table and only the lower candidates throw again. At Chouette automatic doubles do not occur when candidates are throwing for position, the doubles not being effective until after the positions are established and a game is actually begun.

Beyond the limitations of a single game it is not necessary that the number of players in Chouette be fixed. Players may enter or drop out of a session at will; one of the most delightful features of Chouette is this flexibility. A newcomer joining a game is expected to start at the bottom of the line of inactive partners.

For each additional player who joins the field against him, the player in the box stands the chance of winning or losing an additional stake.

With a large field of opponents against him, several doubles, and the possibility of the game ending in a Gammon or Backgammon, it may be seen that the player in the box runs considerable hazard, but at the same time he has a chance for a large coup. A run of luck which results in the player in the box retaining his place for a number of successive games will usually mount into very large figures. However, a player in the box is never exposed to the risk of a similar run of bad luck, for at his first loss he surrenders his place and retires to the field. This protection is an excellent feature of Chouette.

PART II

The General Strategy of Backgammon

A novice at Backgammon should give no consideration to the strategies of the game until he has acquired a sound knowledge of the mechanical rules of play and an easy familiarity with his board.

Like the five-finger exercises which prepare the embryo pianist for his future preludes and fugues, a certain amount of mechanical practice is essential to a competent game of Backgammon.

In the beginning the best way to acquire facility is to practice alone. As a start train yourself to set up the men without reference to a diagram, locating the inner tables first on one side and then on the other. The next step is to study your board, observing certain of its features which will aid you to speed up your moves.

Eye Training and Coordination

Remembering that the point from which you start is never counted, and noting that the points of the board are in two alternate colors, you will see that a man moved on the cast of an even number must land on a point of the same color from which he started; while a man moved on an odd number must arrive on a different color point.

Observe also that a throw of five will always carry a man from one end of the table to the other and that a move of six is bound to take him into the adjoining table.

Now, for practice in moving, play alternately the Black and White men, throwing the dice and making the moves as in a real game. Follow carefully all the rules of play but do not at first attempt to exercise any strategy. From the outset school yourself to think of your moves in the units of the numbers thrown; for example, five and three, or three and five, never eight. And be sure to measure these moves with your eye, never by counting off points with your finger or with taps of the man you are moving. Shifting two men with the single motion of one hand speeds up your game and is an easily acquired knack.

As this preliminary work is solely for the purpose of eye training, coordination, and speed, between throws of your dice occasionally take a general survey of the board and tell yourself as promptly as possible what throws will enable you to strike adverse blots, cover exposed men, and so on. Once acquired, this habit of quick observation will prove inestimably valuable to you in actual play.

Strategic Positions

When you have reached the stage of easy familiarity with your board and have gained a certain speed in your moves, you are ready for a general outline of the strategy of play. The first steps in strategy can also be taken in solo practice.

For the purpose of clarifying some of the general and specific strategy of Backgammon, and doing away with the monotony of such repetitious terms as “Two men from Black’s inner table,” “One man from White’s outer table,” and so on, I have given the men in the various positions military titles, suggestive of the part they play in this “Little Battle.”

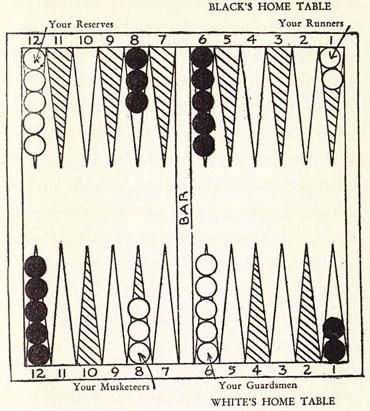

From this time on we shall refer to the men by the titles given in Diagram IV.

Diagram IV

You Are in the Position of White

As a beginning, observe the various positions of your men in relations to their goal, your home table. The five Guardsmen are already home, and, naturally, it is to your advantage to keep them there. As they cannot move backwards, the Guardsmen must remain in your home table unless in spreading them on different points you should leave blots and be taken up. This contingency may have to be risked at certain times during the game in order to establish strategic positions or to take up enemy men. It would be entirely inadvisable to keep this long line of Guardsmen indefinitely idle. Some of them must be brought into play, but until the last stages of the game are reached, at least two should remain to guard the vital Six Point.

As to the men outside, the handiest to bring home are of course your Musketeers. Your interest in these three, however, does not lie in the accomplishment of so easy a feat, but rather in utilizing them for the establishment of strategically significant points.

The most essential points for early establishment are your Five and Bar points. Once you succeed in covering these points, you have, with the already protected Six Point, a solid and formidable barrier which renders your opponent’s escape from your inner table extremely difficult. Your Four Point is another important one. For builders in fortifying all of these points it is advantageous to bring up some of your Reserves.

Later in the game you will probably need to establish your lower points, but at the outset it is bad strategy to advance your men to these farthest positions where they are practically out of play for the rest of the game. Remembering that the rules of Backgammon force you to move whenever possible, even though you may prefer not to do so, you can realize the awkwardness which might result from having a number of your men inactive.* In consequence, you would be forced to make numerous and repeated blots with your outside men, while your opponent, assuming that he had more wisely kept his men in play, would be able to move them toward his goal in a sort of mass formation which generally leads to success in Backgammon. This brings us to the most vital factor in winning play at Backgammon. It is that while progress is necessary it is not so important as position.

When a superior player seriously wishes to offer a handicap he usually allows an inexperienced adversary to take the first move with double Aces.

Should you be tempted, as are most novices in Backgammon, to rush your men helter-skelter into your home table, remember the old proverb which is so applicable to this ancient game that it might have been originated for it:

“Haste makes waste.”

As said before, your five Reserves should if possible be advanced to establish strategic positions, or to be utilized as future builders of significant points.

As for your Runners, they seem so lonely and so dangerously far from home that your instinct may prompt you to drag them out at the first possible opportunity and hurry them, whether or no, around their long line of march. Before you yield to this impulse, stop to consider the possible advantages which may be derived from the unique position of your Runners. Recalling that your own most important positions are your Five Point and your Bar Point, you must realize that the case is the same with your opponent. On a throw of fortunate doubles, your Runners can be advanced to preempt one of his most salient points before he has succeeded in doing so. When you wrest one of these important points from your adversary you gain a still further advantage in having your Runners where they can readily escape from his stronghold.

All of these considerations render your establishment of the opponent’s Five Point, Bar Point, or Four Point of only secondary importance to the covering of your own.

When unable to establish advantageous enemy points with your Runners they may still be put to very good use in breaking up your opponent’s efforts to fortify his home table, though you should neglect no favorable opportunity to bring them safely out of hostile territory.

Later, as you develop your skill and become conversant with the oblique strategy known as the Back Game, you will learn of another purpose for which your Runners may be utilized. But before concerning yourself with the intricacies of the Back Game it is well to become familiar with all the usual types of Forward Games.

Opening Moves

For a game so largely dependent upon chance as is Backgammon, it is impossible to lay down hard-and-fast rules of play. With the progress of a game, its aspects constantly change, new factors appear and disappear, a single throw of the dice may be sufficient to cause an overwhelming shift of the odds in favor of one player or the other.

At the same time, certain general suggestions may be given which are bound to prove helpful to the novice. Then, too, it is possible to learn how expert players utilize their opening throws to the best advantage in moving their men. Any Backgammon player can readily familiarize himself with the best strategy in opening moves, most of which was settled upon more than two hundred years ago. With all of our modern improvements in Backgammon, little change has been made in the tables of best opening plays as listed by Hoyle, and played, as notes a writer of his day, “in all the politest of polite circles.”

With the addition of a few modern innovations and some comments of my own, I have arranged these classic opening moves in a manner which I believe will greatly facilitate their study.

A Special Arrangement of the Classic Initial Moves

With Some Modern Innovations and Comments

In the special arrangement of initial moves shown below, it will be noted that doublets are included.

As the first move is made by the higher player using the combined numbers of his own and his opponent’s throw, it can never occur on doublets. But the second throw may be doublets, and at that stage the original positions are not apt to be materially altered. Also, in cases where alternative moves are shown, it is highly probable that one or another can still be made to advantage, even after two or three throws.

[All favorable opening moves are starred (* Good, ** Very good, *** Excellent) according to the relative advantages of the throws. It will be noted that all doublets offer the opportunity to establish one or more points and are all more or less advantageous throws.]

Doublets

| *** Double Aces: |

Two Guardsmen to your Five Point and two Musketeers to your Bar Point. (The advantage of establishing two such important points more than offsets the risk in leaving a blot.) |

| ** Double Twos: |

Two Guardsmen to your Four Point and two Reserves to your Eleven Point. |

| ** Double Threes: |

Two Musketeers to your Five Point and two Guardsmen to your Three Point; or two Reserves to your Bar Point; or two Musketeers to your Five Point and two Runners to opponent’s Four Point. (All plays are about equal in choice.) |

| *** Double Fours: |

Two Runners to opponent’s Five Point and two Reserves to your Nine Point; or two Reserves to your Five Point. (Both plays are about equal in choice.) |

| * Double Fives: |

Two Reserves to your Three Point. |

| *** Double Sixes: | Two Reserves to your Bar Point and two Runners to opponent’s Bar Point. |

Mixed Numbers

| Six-Five: |

One Runner as far as he will go. (He is safe with your Reserves. This play is called “The Lovers’ Leap.”) |

| Six-Four: |

One Runner as far as he will go. (On this throw you could establish your Two Point, but it is poor strategy to advance your men so far, putting them out of play.) |

| Six-Three: |

One Runner as far as he will go (a blot but not dangerous). |

| Six-Two: |

One Reserve to your Five Point (a blot but justified by favorable chances of establishing valuable Five Point on next throw). |

| ** Six-One: |

One Reserve and one Musketeer to establish your Bar Point. |

| Five-Four: |

Two Reserves to your outer table; or one Reserve to join Musketeers and one Runner to opponent’s Five Point (a dangerous but sporting play). |

| Five-Three: |

One Musketeer and one Guardsman to establish your Three Point; or one Reserve to your Five Point (a sporting move; recommended only for experienced players). |

| Five-Two: |

One Reserve to join Musketeers and one Reserve to your Eleven Point (a blot but not dangerous). |

| Five-One: |

One Reserve to join Musketeers and one Guardsman to your Five Point (a dangerous blot but justified by chance of establishing valuable point). |

| Four-Three: |

Two Reserves to your outer table; or one Reserve to your Nine Point, and one Musketeer to your Five Point (the more sporting move). |

| * Four-Two: |

One Musketeer and one Guardsman to establish your Four Point. |

| Four-One: |

One Reserve to your outer table and one Guardsman to your Five Point (a sporting but constructive move). |

| Three-Two: |

Two Reserves to your outer table; or one Musketeer to your Five Point and one Reserve to your outer table (the more sporting and more constructive move). |

| ** Three-One: |

One Musketeer and one Guardsman to establish your Five Point. |

| Two-One: | One Reserve to your Eleven Point and one Guardsman to your Five Point (a sporting but constructive move.) |

I would advise against memorizing these plays by rote but would suggest rather that you set up your board as for the commencement of a game, place the list of opening moves beside it, and then throw the dice and move the men according to the correct position as indicated for the more conservative plays.

Without considerable experience in actual competition it is better for a player to adopt a conservative policy. The most daring moves should, in the main, be confined to those well versed in the technique of the Back Game.

After each move replace the men, throw the dice, and move again from the original set-up. As soon as you feel familiar with the moves, try making them without reference to your list. It is surprising how quickly the mechanical action of moving the men fixes the plays in your mind. As indicated, the best throws are those which cover the most points, establish your own or your opponent’s Five or Bar points, or some other important position.

All doublets are favorable because they offer opportunities both for definite advancement and for establishing points without, as a rule, leaving blots. The poorest of the doublets are the fives, which can only be utilized to establish one rather unadvantageous position, your Three Point. But double fives, on the other hand, do result in very substantial advancement.

Among the mixed number are a few auspicious opening throws such as six-one, three-one, and four-two. But the majority of mixed numbers afford no really constructive opportunities. It will be noted that on many of these a play is advocated which leaves one or more avoidable blots. The purpose of such hazardous moves is usually to lay the foundation on which strategic positions may be built in future plays.

At the outset of a game you should bend every effort toward establishing points which will yield you some advantage. And in this early stage you can risk being taken up with the positive assurance that the enemy’s table will not be so fortified as to prevent your quickly reentering.

Of course the ideal game consists in several perfect opening moves followed by an entirely safe and swift progress of all your men to your home table. But the remarkably favorable run of dice which would be necessary for such a consummation rarely, if ever, occurs. Much more often we begin a game with a string of unproductive throws which we are forced to make the best of by utilizing them to chance the improvement of our future situation.

During the course of every game you will probably be forced to take a number of risks. As said before, it is far preferable to take them early while there is some hope of establishing a good position for yourself, and while your opn0nent’s table is still comparatively free.

Experienced players always prefer to play their unpropitious early throws in a manner to determine at once whether they can obtain a foothold for a favorable Forward Game or will be forced to resort to Back Game tactics.

If a player is to adopt a Back Game, he will do well to realize the necessity for it as early as possible.

In the list of opening moves, unnecessary blots are never recommended unless there is some definite reason for making them.

When in your practice of opening plays you reach the point of automatically responding to any throw of the dice with a swift, accurate move, you have progressed about as far as is possible in solo practice, and must acquire your further proficiency in actual games.

General Strategy

Beyond the opening plays it is obviously impossible to give specific advice. Once a game is under way, each play so alters the situation that certain moves, considered advantageous for the opening, might become extremely disadvantageous, or might be rendered impossible by the opponent’s blocks. As long, however, as no radical change from the original set-up has occurred, the throws starred (*), (**), (***) in the lists should usually be followed. In throwing double aces for instance, during the earlier stages of the game, you would not be likely to have a better move than the establishment of your Bar and Five points, provided of course that these positions were still free. If, however, the enemy Runners are out of your inner table, establishing your Bar Point is somewhat like locking your stable door after the horses have escaped.

In the majority of games, points established in your home table remain important until the last stages; for these points not only block the escape of enemies from your home table, they shut out those who have been captured and retired to the bar.

As a game gains headway you are forced to rely more and more on your own judgment in the utilization of your casts. The following suggestions may prove a general aid in developing this judgment of specific situations.

Progress, Protection, and Position

Though it is true that you can never win a game of Backgammon unless all of your men have made sufficient progress to arrive in their home table, progress is not your main consideration. The factors of safety and position are even more important.

As much as is compatible with the efficiency of your game, your men must be watched over and protected in their march to the home table. “Cover your man!” is an old Backgammon adage which should be kept well in mind. On the other hand, do not become so concerned with safety as to forget that position is still more of a consideration.

For the sake of building a favorable position you must even after the opening moves continue to take some chances and voluntarily make certain blots which promise to establish points. And remember that every advanced point established increases the safety of your men because it provides them with a secure resting place on their line of march.

In short, you can never go far wrong if you remember that there are three important P’s of Backgammon, Progress, Protection, Position, and that the greatest of these is Position.

Overcrowding Points

“Safety First” is a poor slogan for winning Backgammon. The policy of the timid soul who just for safety’s sake allows his men constantly to go into huddles usually reacts as a boomerang. For sooner or later a break must occur and, unfortunately, it is seldom sooner but usually later, when the points of the adversary’s table are so thoroughly obstructed that a man on the bar has little chance of reentering the game. The rules of Backgammon permit an unlimited number of men to be piled up on a single point, but the best policy of the game is against the accumulation of more than three.

Leaving Blots

In almost every game of Backgammon there occurs a certain psychological moment when a daring risk may turn the tide of luck in your favor. Keen judgment in recognizing the fine points on which the success of such bold plays is balanced is undoubtedly the keynote of a masterly game of Backgammon. Such judgment can only be bought with experience and such opportunities must be sensed; it is impossible to point them out.

One simple and very sound general rule for guidance in taking risks is this: When your position appears distinctly better than your opponent’s, be careful about taking unnecessary risks, but when yours is the adverse position, risk any chance, short of being Gammoned, which promises to improve your situation.

When contemplating leaving a blot, you should figure the chances of having your man taken up. Obviously, your opponent can more easily hit a man which he is able to reach with a single die (that is with some number under seven) than with double dice (a number over six). So it is readily seen that the odds against a man’s being hit vary with his distance from the source of danger. These odds are fully shown in the following table, one of the many valuable calculations of chances bequeathed to Backgammon by Hoyle.*

The Odds Against Hitting a Blot

With a single die, it is —

- 25 to 11 against hitting a man 1 point away.

- 24 to 12 against hitting a man 2 points away.

- 22 to 14 against hitting a man 3 points away.

- 21 to 15 against hitting a man 4 points away.

- 21 to 15 against hitting a man 5 points away.

- 19 to 17 against hitting a man 6 points away.

With both dice, it is —

- 30 to 6 against hitting a man 7 points away.

- 30 to 6 against hitting a man 8 points away.

- 31 to 5 against hitting a man 9 points away.

- 33 to 3 against hitting a man 10 points away.

- 34 to 2 against hitting a man 11 points away.

- 33 to 3 against hitting a man 12 points away.

It will be observed that the odds are always against the man’s being hit, whether with one die or with two.

The table need not necessarily be memorized. The important thing to keep in mind is that it is more difficult for your adversary to hit a man very close to him or very far from him than one at about middle distance. Therefore, in choosing between two possible positions, in one or the other of which a blot must be left, other things being equal, leave the blot out of reach of a single number (the farther away the better*) or, failing that, place it as close as possible to the adversary’s man. It goes without saying that the more enemy men spread out before you on your line of march the greater your chances of being taken up.

Probably the one most important guide to the advisability of leaving an avoidable blot is the appearance of your adversary’s home table. Every point covered lessens your chance for reentering, therefore increases your danger in making a blot.

Taking Up Enemy Blots

A warning must be given against an error which occurs even among fairly experienced players. This is the mistake of hitting any and every possible blot, Without stopping to think whether or not it is advantageous to do so. Here, as in every other move in Backgammon, discretion and judgment are essential. Do not regard every possible captive as an asset; in many situations an enemy on the bar proves a liability.

One of the situations which make it inadvisable to take up an enemy occurs when the blot is in your own table and to hit it you must use a man far advanced, leaving him, in turn, unprotected. Such a trade is a poor one because the enemy taken up has lost no ground, while you give him the chance of reentering and hitting your well-advanced man.

Taking the reverse of the above picture, it is greatly to your advantage to hit an opponent’s man in his home table. Also, of course, the opportunity to hit an opposing man and establish a point on the same throw should rarely be neglected.

The most generally advantageous time to take up blots comes after your home table is so well fortified that the enemy may have to cool his heels on the bar indefinitely while you progress and further strengthen your position.

Whenever you have succeeded in capturing two or more enemies, hasten to spread some men in your outer table, ready to pounce upon and recapture the helpless entrants. To clarify this bit of particularly valuable strategy, remember that your opponent can make no move before entering all of his men from the bar. In short, with two or more of his men on the bar, you are in a position to hit him when he cannot hit back.

Entering from the Bar

There is little to be said concerning entering men who have been taken up, because as a rule there is small choice in the matter. You must enter your man on a point corresponding to a number shown on one of your dice, and usually you are delighted with any chance to do so.

When, however, your throw happens to offer a choice of two points of entry on either of which you must leave a blot, it is best to come in on the farthest point, thus forcing your opponent to push a man practically out of play if he wants to retake you.

The opportunity to enter on a point already occupied by one or more of your men is, of course, advantageous.

Running For Home

In racing for your home table, if you are past all of your opponent’s men and no longer need be concerned about making blots, be sure to utilize all of your throws to the best advantage.

For example, always, if possible, use a throw to move a man into the next table, rather than simply to advance a man from one point to another in the same table.

When it comes to entering your home table (unless you are merely racing to prevent a Gammon), use your throws to spread your men as much as possible. Having the points in your home table well balanced gives you a distinct advantage in throwing off.

Guarding Your Outposts

Unless you are playing a running game with the decided advantage in progress, do not move all of your men past your adversary’s. A premature withdrawal of your forces from your enemy’s territory leaves him to move at will and make blots without hazard. Such unwonted freedom is an advantage which might readily present him with a game.

Also, when playing a game in which your opponent has gained so distinct a lead that you are hard put to avoid being Gammoned, leave two of your men on his Ace or Two Point. They prevent his bearing off to advantage, forcing him for safety’s sake to move up rather than throw off. Sometimes he cannot avoid leaving a blot which you are lucky enough to hit. In any case, by thus hampering his throwing off you will usually gain sufficient time to rush all of your more advanced men home and then, making a break for it with the others, dash them over the bar in time to save your skin.

Bearing or Throwing Off

In bearing or throwing off when your inner table is free of enemies, it is advisable to have your men well spread so as to gain every advantage from your casts. With a free table, always bear every possible man. Never make the choice of moving instead of throwing off unless the enemy is still lurking in your table.

When you are attempting to throw off under the handicap of an enemy block on your One or Two Point, your situation is dangerous. Without discretion in utilizing your casts, you are apt to find one or two of your men on the bar, with your bearing-off process suspended until they can reenter and make the long trek back home. Such a risk can best be avoided by moving up your men instead of throwing them off.

Playing the Favorable Odds

As to how much practical value lies in playing for the chances of the dice and the various odds of Backgammon, a player must decide for himself.

Some Backgammon players prefer to be guided entirely by what they term “hunches,” playing their luck rather than the mathematical probabilities. Such players claim their success lies in the simple process of making very daring moves or playing with extreme conservatism according to whether they feel the luck to be for or against them.

But when we remember that gambling casinos are expensively and profitably maintained by the mere fact that the odds of the games conducted are always with the house, it would seem that, in the long run, success at Backgammon must result from the combination of nice judgment with a systematic play of the favorable odds.

The science of betting lies in offering odds that look favorable, but give the bettor a little the best of it in the long run.

At Whist it is said that Lord Yarborough made a tidy fortune by offering any player odds of 1,000 to 1 that he, the player, would hold some card above a nine.* On its face this bet looks highly favorable to the taker but the actual odds against such a hand are 1,827 to 1.

The Chances of the Dice

To find out the chances of any event we must first ascertain all the things that might happen and, second, figure out those which would be favorable to the event. Then one calculation must be deducted from the other; the two figures that are left giving us the odds. For example, a die has six faces numbered from one to six. The chances of throwing any of these numbers is one out of six, hence five to one against the throw.

In Backgammon where we throw two dice, the calculation of odds is a more complicated affair. Suppose that we want to know the odds of a blot being taken up on a throw of six. First we must figure out how many different throws can be made with the two dice, and then how many of these will result in a throw of six.

As six different throws can be made with one die, it is plain that any of these can be combined with any of the possible six throws of the other die so as to make a total of thirty-six possible throws.

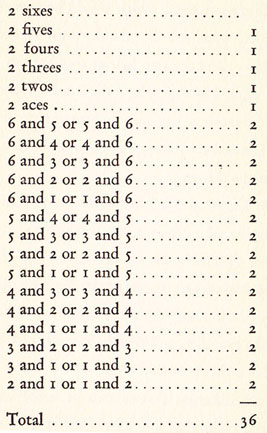

The Thirty-Six Possible Throws With Two Dice

It will be noted that while all other numbers appear twice, each doublet is counted only once. A doublet can be thrown in only one way, because both dice must show the same number. But throws of mixed numbers can be made in two ways. To clarify this principle, instead of throwing your two dice with a single motion, throw one and then the other. The first die may show a 6 and the second a 5. Now throw them again, the same way. The first die may show a 5 and the second a 6. Thus a throw of 6-5 can be made in two distinct ways.

Now we know that at Backgammon there are thirty-six possible throws and we want to find the chances of a blot being hit on a throw of six. We must figure that a throw of six can be made in any one of the following ways:

Possible Throws of Six on Two Dice

| Possible throws of two dice | 36 |

| Possible throws of six | 17 |

| 19 |

Hence the chances of a throw of six are seventeen for to nineteen against.

A glance at the following table shows that while the chances of a six are more favorable than the chances of any other number, the odds are always against throwing any particular number.

Here are the chances against throwing numbers from one to twelve:

- The odds are 2 5 to 11 against throwing a 1.

- The odds are 24 to I2 against throwing a 2.

- The odds are 22 to 14 against throwing a 3.

- The odds are 21 to 15 against throwing a 4.

- The odds are 21 to 15 against throwing a 5.

- The odds are 19 to 17 against throwing a 6.

- The odds are 30 to 6 against throwing a 7.

- The odds are 30 to 6 against throwing an 8.

- The odds are 31 to 5 against throwing a 9.

- The odds are 33 to 3 against throwing a 10.

- The odds are 34 to 2 against throwing an 11.

- The odds are 33 to 3 against throwing a 12.

Accurate as are the above figures in the abstract, they only partially cover the odds against an opponent’s hitting our blot. For here another element must enter into our calculations. It is possible that the adversary may throw the requisite number for hitting a blot but his move may be prevented by our intervening blocked points.

If we wish to attain a really close accuracy in calculating the chances at Backgammon, we must first know the odds against a certain number’s being thrown and then take into consideration that each one of our blocked points between the opponent’s man and our blot further decreases the probability of our being hit.

PART III

The Technique of the Three Forward Games

It is customary to speak of different strategies of Backgammon in terms of “games”; the Running Game, the Blocking Game, the Shut-out Game, and, lastly, the Back Game. The first three are further classed together as Forward Games. The Back Game, however, is so very distinctive and dissimilar from any other strategy that it stands in a class by itself.

While the initial methods of the various games are different, it must be noted that the strategy of one very often becomes parallel or completely merges with another. These analogies are apt to confuse the student of Backgammon and lead him to despair of mastering its finer points. But remembering that Backgammon has but one simple objective, to clear your board before your opponent has succeeded in clearing his, it must be realized that though there may be different ways of setting about the accomplishment of this task, somewhere along their course those ways must meet.

Backgammon is so much a game of sharp changes, sudden shifts of luck which bring us success or failure where the reverse seemed certain, that a warning must be given against attempting to decide on any particular type of play at the outset of a game.

A master of Backgammon never commits himself to a definite type of strategy, sticking to it whether or no. Rather he is an opportunist, always flirting with his dice, always ready to shift his tactics in response to their caprices. In a word, flexibility is the keynote of winning Backgammon. Nothing is so destructive as the adoption of an unswerving pattern of play.

The best way to decide upon a particular policy is simply to throw your dice, follow the most favorable initial moves (by this time, incidentally, you should have progressed beyond the most conservative ones), and play along for a bit according to the best general policies of the game; then stop and make a comprehensive survey of the board. Ask yourself where you stand and where your opponent stands, and according to your position and his, adopt some definite policy of victory. At the same time, always be on the alert for a change in situation which may dictate a change in your policy.

With the descriptions of the various game strategies will be given the situations which would logically prompt their adoption. The diagrams will prove more helpful if the positions are set up on an actual board and the plays followed out.

The Running Game

Simplest and most clear-cut of the three Forward Games is the Running Game. As its name implies, it consists merely of a straightforward race to your home table.

The Running Game should usually be attempted when you have started with very favorable dice, have gained a decided advantage over your opponent, and have succeeded in bringing your Runners safely out of hostile territory. An initial throw of double sixes followed by several large throws usually favors the policy of a Running Game.

Once you have definitely committed yourself to a Running Game, simply forge ahead as rapidly as is compatible with safety. If possible, avoid taking up enemy men because in reentering they will only prove obstacles to your progress. Jump over blots and get past adverse men, when you can.

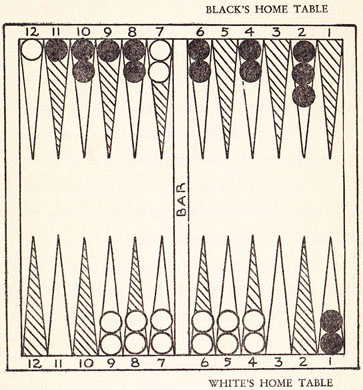

In Diagram V White is playing a Running Game with every promise of success:

Diagram V

A Running Game

It is White’s move. He throws double twos. He could take the whole move with his two Reserves, safely hitting Black’s blot. But having an adversary on the bar might be extremely disadvantageous. So White only advances his Reserves as far as his Eleven Point, and then moves two men from his Seven Point into his home table.

In Diagram V, White is fortunate in having no enemies to hamper the safe landing of his men in his home table. When some of the enemy’s men hold a low point in your home table, a Running Game is more difficult to carry off.

The Shut-out Game

When your opponent’s two Runners are split up on the low points in your home table, and you have several established points there with some Reserves in your outer table, your stage is attractively set for the inauguration of a Shut-out Game.

If, before either of the enemy men escapes, you can throw a doublet or any combination of numbers which enables you to hit one of the blots and establish the point at the same time, nothing but bad luck in your throws or very good luck in your opponent’s should defeat you.

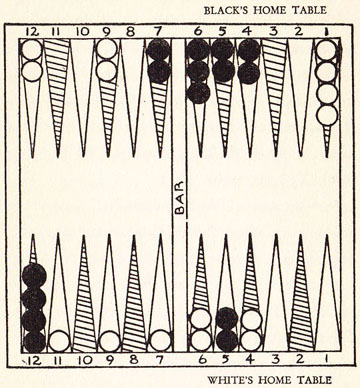

In Diagram VI White, who has the next throw, is shown in a promising position to launch a Shut-out campaign.

Diagram VI

White Should Play for a Shut-out

For the sake of easy illustration we will suppose that White is highly favored with the ensuing throws:

White, throwing six-three, proceeds to hit the nearest block with a man from his Six Point and then to cover his man with a move from his outer table.

Black throws five-four and cannot enter. White throws double threes and advances two men from his Bar Point to take up Black’s remaining blot and at the same time establish another point.

Black throws four-one and cannot move.

White throws six-four and hastens to establish his last free point (his Two Point) with a man from his Six Point and one from his outer table.

Now White’s objective is attained. The complete closing of his table shuts Black’s men out from any possible play. There is no use for Black even to throw his dice, while White can play as he chooses. Herein lies the great value of establishing a shutout. While Black is helpless, White has the freedom of the entire board. This feature of the Shut-out makes it the most generally successful game when it can be established.

Of course, White’s only concern is to bring his two Runners out of Black’s table. This cannot be accomplished without some care and a little luck. For though White has nothing to fear in making blots, his danger lies in finding his outside plays blocked so that he may be forced to break up his perfect Shut-out. Against this contingency, the third man still in play acts as a safety valve, offering White leeway for using up his throws should his Runners be blocked by Black’s established points.

To illustrate the use of White’s “safety valve” on his Nine Point, we will assume that White’s throws are as follows:

| 1st Throw: | Six-Four: Both Runners advance. |

| 2d Throw: | Two-Three: Rear Runner advances. |

| 3d Throw: | Double Aces: Both Runners are blocked; move is taken by advancing safety valve to Five Point. |

| 4th Throw: | Two-One: Forward Runner advances on the two. One is played by moving safety valve to Four Point. |

| 5th Throw: | Five-Four: Rear Runner advances to Nine Point. |

| 6th Throw: | Four-Three: Rear Runner advances to Six Point. |

| 7th Throw: | Two-One: Last man is brought home. |

The value of White’s safety valve appears on the third and fourth throws where without this available man White would have been forced to break his blockade. This is one of the many situations which show the reason why it is poor strategy early in the game to advance one’s men too far, and why it is desirable to keep as many as possible in free play.

Now that White’s men are all across the bar, if he wishes to assure his game without further risk, he should not immediately begin to throw off but should use all available numbers safely to move up from his Six Point. This plan opens his table at a point where the enemies entering from the bar will be beyond all of his men and powerless to hit them; then as soon as Black’s men have entered, White could proceed to throw off helter-skelter without fear of blots.

Unless Black is blessed with some high numbers and doublets, White stands to win the further advantage of a Gammon.

An experienced and daring player, having established a Shut-out and brought all of his men home, will often refuse the safe finish, choosing rather to throw off his men in a deliberate attempt to Gammon or Backgammon his opponent. As such a measure always risks the danger of having to leave one or two blots which may result in the loss of an otherwise sure game, the advisability of taking the gamble is always a question.

The Blocking Game or Side Prime

While the success of all Forward Games is largely dependent upon the good fortune of your dice, it is true that some varieties of the Forward Game depend more on luck than others. For instance, the very propitious throws required for a successful out-and-out Running Game make it the least usual of the three.

The most frequent policy employed in Forward Games is that of trying to prevent the escape of your opponent’s Runners from your home table. When a perfect blockade is effected, with his Runners shut off from every possible exit, you are said to have established a Side Prime. A Side Prime always shows six consecutive blocked points.

The establishment of a Side Prime should usually be attempted when you have succeeded in covering your Five and Bar points, have installed some of your Reserves as builders in your outer table, and your opponent’s Runners still remain in their original place on your Ace Point, while your own have escaped from his home table.

Diagram VII shows White, who has the next move, in a very favorable position to try for a Side Prime.

Diagram VII

Favorable Position to Attempt a Side Prime

If, before White establishes his Side Primer, Black should split his runners on a low throw, say a two and a one, White would abandon the policy of the Side Prime and shift to the strategy of the Shutout. White’s next cast, however, would almost certainly enable him to make the Four Point in his home table or some other valuable point, and with each new barrier Black’s escape would become more and more difficult.

Diagram VIII illustrates White’s Side Prime fully established. With six successive blocked points.

Diagram VIII

White’s Side Prime Established

As the highest possible throw of a single die is six, it is impossible for Black’s men to escape until White is forced to open a point.

Of course, a Side Prime can be established on other points, and naturally it may serve to block the play of any number of the opponent’s men.

As shown above, White has now gained the entire freedom of his outer table. While Black can move elsewhere, he cannot reach a blot in that territory. White’s first concern should be to get the men from Black’s outer table safely to his own. On his way White should endeavor to take up one more of Black’s men (having an additional man out of play will greatly embarrass Black) but should avoid taking up further blots, as more than three enemies in one’s home table constitutes too great a menace.

It may be observed that White’s tactics at this juncture become those of the Running Game and the end play of a Shut-out, showing how all the types of games parallel and merge into each other at times. With the safety valve on Black’s Twelve Point, White is almost insured against having to break his Side Prime. Only bad luck can beat him now.

As a matter of curiosity in seeing the effectiveness of a Side Prime, set up your board as in Diagram VIII and, following the general strategy of the Shut-out play, throw your dice and play the alternate moves of White and Black to a finish. You will observe how having two or three men out of play will usually force Black to clear the high points of his home table, so that, even if White happens later to be taken up, he can quickly reenter and effect his escape.

PART IV

The Back Game and Counter-Back Games

From the description of the three types of Forward Games, it can be seen that they are all naturals, that is evolved from the inherent necessities of Backgammon.

Two inexperienced players setting out with merely a mechanical knowledge of the game, simply by throwing their dice and trailing along with them, would unconsciously develop some form of a Forward Game.

The Running Game is the most usual type evolved from mechanical play. But it is not uncommon for a novice at Backgammon, throwing ideal dice, to be automatically carried to victory with a perfect Block or Side Prime which he has quite unintentionally established.

On the contrary, the technique of the Back Game is entirely unnatural. To bring it to a triumphant conclusion one can rarely just follow one’s dice. It requires deliberate intention and, in its initial stages at least, demands a complete reversal of the strategy of any type of Forward Game.

As the primary object of all Forward Games is to advance one’s men while keeping them as well guarded as possible, the purpose of the Back Game is to retard one’s men as much as possible While exposing them to every conceivable hazard.

The why of such oblique tactics is this: A player beginning a game with poor casts finds himself far behind a luckier opponent who has made definite progress and established several salient points. Realizing that with such an unequal start there is little probability of his winning a straightforward race, the less fortunate player sees his only chance in trying to harass his opponent’s men, to trip them up, and set them back to begin all over again. Successfully to carry on such a campaign he must have his men so placed that they will meet as many of the opponent’s as possible, in short to keep them back — preferably in the adversary’s inner and outer table. Hence the policy of leaving promiscuous blots, hoping that the adversary will be forced to hit these lone men and set them back.

Because the greatest difficulty in the Back Game is to keep far enough behind, its fortunate conclusion is usually dependent on early planning. For many reasons there is but small percentage in favor of a Back Game which is inaugurated after your men are too advanced. Unless your Runners still remain in their original position on your opponent’s Ace Point, none of your men have advanced beyond your Four Point, and some others are in the opponent’s inner or outer tables, the likelihood of victory with a Back Game is not overly promising.

In Diagram IX White has elected to play a Back Game:

Diagram IX

White Is Shifting into Back Game

White throws a two-one. Even though his cast would enable him to eliminate two blots, he refuses to do so. Instead he advances one man from Black’s One to his Two Point, and splits up his men on Black’s Nine Point. Part of White’s object in the last move is to spread his men so that they will act as “catchers” for Black’s homecomers; he also hopes that Black will be forced to take up one of the outside blots, which with good luck could be entered on Black’s Two Point.

If White is successful in this strategy he will have five men prei-Smpting Black’s two farthest points, ready to meet all comers and capture practically any blots in that region. This advantage, coupled with the fact that all of his men are in play (none being pushed too far into his home table), places White in the ideal Back Game position.

Now White must bend every effort toward catching one of Black’s hindmost men, and while trying to pick up another, forcing him to reenter and catching him again. When White has secured two captives he should keep his men spread as catchers in his outer table and should also try to establish additional points.

Especially should White endeavor to block the points just outside his table where Black could escape with large doublets, for large doublets would enable him to push ahead of all White’s catchers.

To show how the various strategies merge into one another, it may be observed that while White is bringing up his men to make additional blocks, he is in a measure playing a Forward Game. But until the balance has swung entirely in his favor, he must retain his stranglehold on at least one of his points in Black’s home table.

Perhaps it would be found interesting to set up the board as indicated in the diagram and play out a few games.

Once having elected the backward strategy a player must stick it out. He should not allow himself to weaken unless the luck of his dice so definitely changes that the shift to a forward policy is obviously his best recourse.

The main reason why most players fail to pull through with a Back Game is that they lose their nerve at the critical moment. Or else when one good throw comes along they become dazzled, believe that their luck has turned, and make a premature shift to forward tactics. In either case disaster is almost inevitable. For at Backgammon nothing so surely courts defeat as a policy of vacillating between backward and forward tactics.

Unquestionably the Back Game adds immeasurably to the science as well as to the interest of Backgammon. Without it, little but the element of luck would remain, for, other things being equal, the player with the better dice would invariably win, and games between players of approximately the same skill would degenerate merely into dice throwing contests.

But a player with a keen knowledge of the backward strategy is, so to speak, ambidextrous. He can make poor dice work for him as well as good ones. And, incidentally, the favorable outcome of the Back Game depends on poor dice just as much as the success of the Forward Game depends on good ones. The high doublets for which the forward player prays are anathema to the backward player.

Considering all the advantages that the strategy of the Back Game affords the player with inferior dice, it might be asked: “Why does not every player shift into these backward tactics at any time that the luck turns against him?” Some of the reasons why such a policy is not apt to be advantageous have been pointed out. The fortuitous Back Games are those which a player presages, not those which he takes to as a last resort toward the close of a hard-luck game. This is why in the opening plays on poor dice experts adopt a daring policy, boldly laying out blots in an attempt to establish a good forward position or to find out immediately if it will be necessary to play a backward game.

Another and even more important reason why the shift to a Back Game should rarely be made when it offers only a forlorn hope is that the backward strategy when unsuccessful enormously increases a player’s danger of being Gammoned. For this reason and because its demands are far more exacting than those of straightforward play, the intense Back Game is peculiarly the province of the expert. Unquestionably the secret of the expert’s uniform success against less experienced players is that a skilled Back Game enables him to discount the dice, snatching victory from bad as well as good ones.

That the oblique tactics of the Back Game are not for the novice is emphasized by the statement of a well-known New York expert, that no player should essay the Back Game until he has had one year’s experience in actual competitive play.

In my opinion this is a matter which must be decided individually. Some newcomers to Backgammon are ready to take up the Back Game before a month’s experience, while others can never successfully encompass its complex strategy. Certainly the tactics of the Back Game demand qualities of initiative and daring which as a rule only time and experience will develop in a player.

In any case, even though he does not intend actually to essay it, a player should acquire a sufficient understanding of the Back Game to defend himself when its rather bewildering strategies are launched against him.

The Counter-Back Game